Making progress, slowly but surely. I’ve spent less time with this painting lately because I’m working on a new webcomic project, and Portal 2 came out. Seriously, buy this game. It’s excellent. More on the webcomic later, once the project is a little farther along.

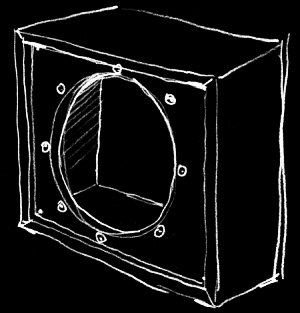

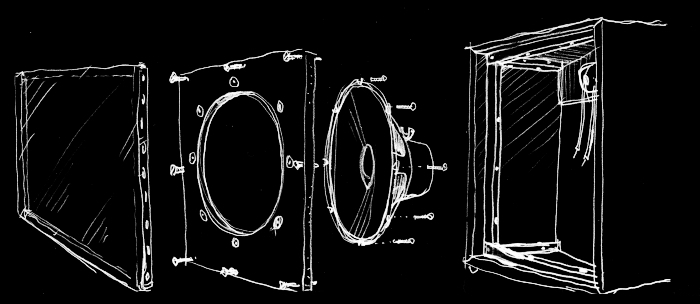

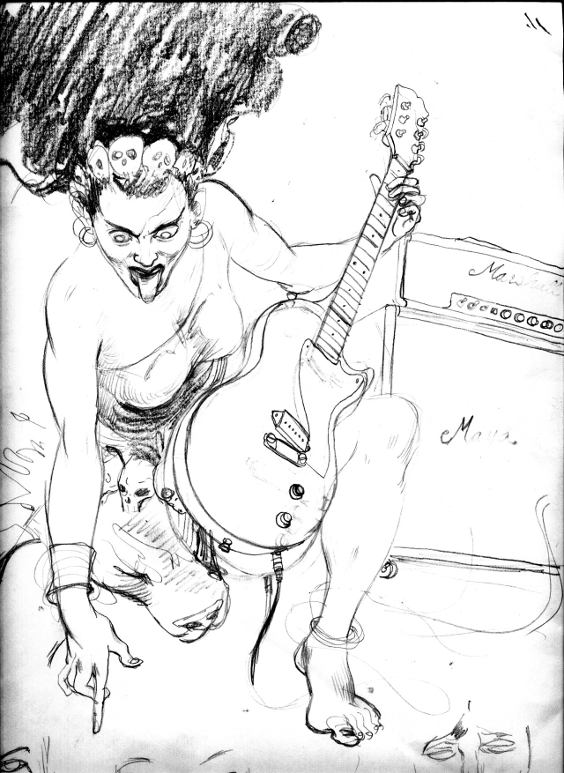

Here’s the final sketch for the painting. You can see that the background and some supporting details are missing or not fully realized. These will come as I paint. Mostly the sketch is to work out the basics. It was important to me that I choose the right guitar and amp combo for this image– it will matter little to most people, but I wanted to avoid just painting a generic “guitar.” I want to render something that a guitar fan will recognize and drool over.

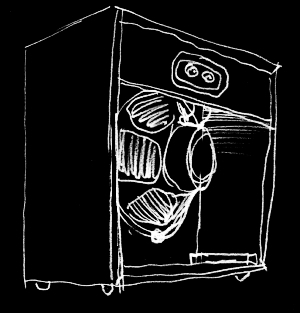

After much hemming and hawing, I finally decided on a 50’s Gibson Les Paul Junior, and a 70’s red Marshall half-stack. The guitar is simple, pared-down to the essentials, but one with a very powerful voice. A true rock guitar. Marshall amps are of course the defacto symbol of rock; big, loud, screaming distortion. The red models they made in the 70’s are gorgeous, and I prefer to paint a big red amp than a boring black one. This guitar and amp combo represents power, aggression and fury quite well, I think.

It’s fairly easy to draw a generic guitar. But to draw a specific model recognizably is particularly difficult, at least for me. I was resigned to using a google image search for reference, but was discussing my choice of equipment with the inestimable Tim Knight, who had something much better in mind. Tim doesn’t have much of a web presence, which is a shame; he’s a cultural asset here in Salem, Oregon. Tim owns and operates Guitar Castle, a vintage guitar store downtown, and co-founded (but is no longer a partner of) Ranch Records, Salem’s best record store. Tim is a great musician; he played and recorded with John Fahey, is a member of the Hundred Dollar Jayhawks, the Nettles, and the Bohemian Enclave, which is his latest project. He helps organize local shows with local talent, and records and advises young up-and-comers. He’s friends with and sold guitars to many great musicians, and has countless great stories to tell.

I love Guitar Castle because there’s always a little bit of history on the racks there. While it is a vintage guitar store, Tim stocks guitars and amps for players, not collectors. For example, I bought a wonderful 1962 Fender Jaguar from him last year. It’s all original, but for one thing: a previous owner had stripped off the sunburst finish and sprayed it with clear nitro. This destroys its value as a collector’s item, but drops it neatly into my price range. A pre-CBS guitar that I can afford and sounds like a dream! (I’ll post more about this guitar some other time.) These kinds of deals make the store unique, and a great place to browse. Tim is also a painter, and his art is on the walls there. He paints scenes and portraits in a “naive” style, and his abstracts (my favorites) are colorful, thoughtful and emotive. (He also has a couple of my paintings hanging in the store. Thanks, Tim!)

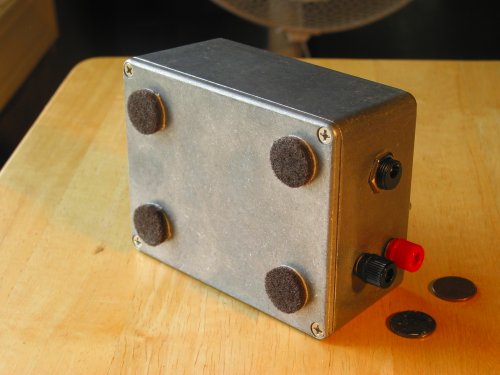

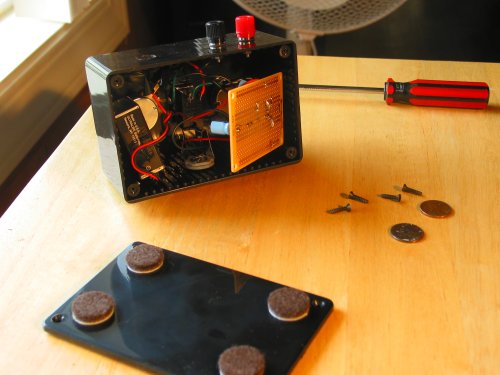

When I told Tim the guitar and amp I had decided would be in Electric Kali, he laughed. “You mean like the ones in my basement?” he said. “Why don’t you shoot them for reference?” Tim Knight is a great guy. I came back a week later with my camera.

Here’s Tim with the Les Paul Junior. It’s no longer in the basement, it’s behind the counter, for sale at a bargain price.

Here’s Tim with the Les Paul Junior. It’s no longer in the basement, it’s behind the counter, for sale at a bargain price.

Tim’s red Marshall. Alas, this one is not for sale.

Tim’s red Marshall. Alas, this one is not for sale.

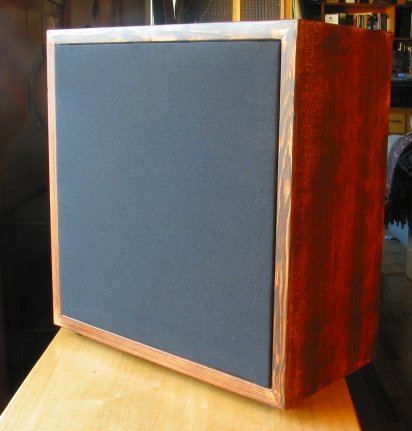

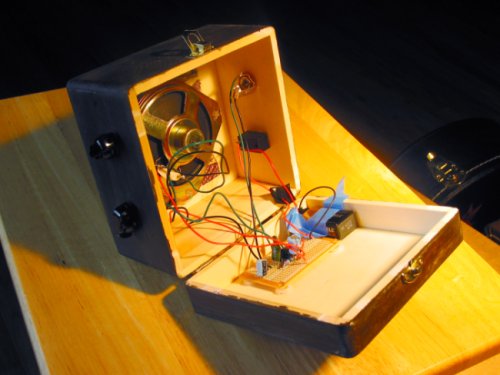

With the reference shot at just the angles I wanted, the sketch came together much faster than cobbling together images from the web. With the drawing done (more or less), I transferred it to a panel, and painted in the basic values using burnt umber and ultramarine. Now I’m roughing color in over the values, using glazes of varying opaqueness. The drawing is still visible a bit under the color, which will allow me to tighten up the detail once I’ve got the overall composition and color where I like it.

I like to work this way rather than make a color rough, because when I change my mind about a color and paint over it, the previous layers all build up to make a richer finish with more depth than if I just started with the right color first. More images to come as I continue to paint!